Part 5: Southland Tales and the re-Birth of the Gonzo cinema

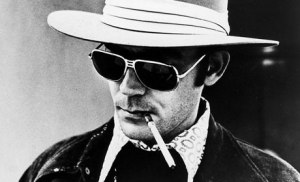

So far I’ve only engaged this film from an academic, literary level, but there are countless sides to this puzzle. Southland Tales is like looking at a fractal reflected through a mirror, and good luck if you can see the whole pattern in one viewing. So I figured for my final piece I would approach the film with the same kind of anti-sense and byzantine logic which propels it. I can think of no better way to summarize anti-logically a stroll down the American nightmare without at least stopping to get directions from the master tour guide, Hunter S. Thompson.

One of the most prolific American authors of the twentieth century, the man—part lizard and part cockroach—was a bundle of drug and alcohol-fueled neuroses. When he could be press-ganged into literary service by his editor, scrambling for pages well past the deadline, he would craft a style of journalism that would force us to rethink the objectivity of an industry which until his time had been considered by most as axiomatic. With Thompson’s writing you were seeing the world through his grimy looking glass—the bottom of a scuzzy shot glass in-between helpings. His America was a vision of hell you could encounter, where politicians would make the Marquis de Sade squeamish and Nixon only missed the Donner party by a few centuries. It was hell, sure, but damn if it wasn’t entertaining.

Looking back on that fear-mongering prologue of Southland Tales, Thompson’s response to 9/11 awakens from its uneasy slumber:

OK. It is 24 hours later now, and we are not getting much information about the Five Ws of this thing.

The numbers out of the Pentagon are baffling, as if Military Censorship has already been imposed on the media. It is ominous. The only news on TV comes from weeping victims and ignorant speculators.

The lid is on. Loose Lips Sink Ships. Don’t say anything that might give aid to The Enemy.

(“September 11, 2001”)

Kelly’s film holds more than a passing similarity to the Gonzo fabrications of Thompson’s journalism.

Louisville reporter John Filiatreau once described Thompson’s work as “generally consist[ing] of the fusion of reality and stark fantasy in a way that amuses the author and outrages his audience.” You’d almost think Filiatreau was referring to Kelly if he hadn’t only just been born that very same year.

Gonzo (as described by Thompson in Fear and Loathing in America: The Gonzo Letters, Volume II): to be “read straight thru, at high speed, from start to finish, in a large room full of speakers, amplifiers and other appropriate sound equipment” (though perhaps don’t take Thompson up on the suggestion that “there should also be a large fire in the room, preferably in an open fireplace and raging almost out of control”, you’ve got the film for that.)

In Gonzo the idea is the focal point. An artistic panopticon, one where you’ll never know which side you’re looking on; that of the prisoner or the guard, system or anti-system. Just like the NSA panopticon Nana Mae runs over American culture, hidden away in her fortress of solitude the entire film, we’re never sure who’s holding the keys—at least we get to leave the office for some fresh air now and again.

In Gonzo the idea is the focal point. An artistic panopticon, one where you’ll never know which side you’re looking on; that of the prisoner or the guard, system or anti-system. Just like the NSA panopticon Nana Mae runs over American culture, hidden away in her fortress of solitude the entire film, we’re never sure who’s holding the keys—at least we get to leave the office for some fresh air now and again.

Like Thompson before, Kelly’s set sail for a new world and discovered a Kingdom of Fear. Like Thompson, who got lost in the jungles of American madness, Kelly was on the campaign trail searching for the American Dream, the great shark hunt, and all he found was a generation of Swine. I don’t think it’s a coincidence the Neo-Marxist propaganda art so closely resembles HST’s own run for sheriff. Death to the weird.

Why am I stressing this connection, and why should you care? This is the birth of the new cinema, the Gonzo cinema. So people didn’t like it, fine, let’s not burn down the theatre and call it a day. Kelly is doing something fantastic here, something unique and inspired. This is the edge of the world he’s found for us, and he’s dared to report there are still places to go.

Keep him in check of course, monitor his progress, get some bloody dispatches from the front—we must make sure he’s not off gallivanting in the New World forgetting why we sent him there. But we did send him there, with every ticket stub we purchased, with every mention of his name. Kell-ey. Cue snowglobe smash.

And like the nurse in Welles’ masterpiece, this is where you come in.

If we did it all before we can do it all again. In the kingdom of our minds, at least, and that’s the only place I know how to reach you. You and I are but one mind each, but together we’re two, and with you we’re three. A pattern is emerging. The memetic spread creeps in its petty pace from day to day. Let us form our hypertext kingdoms. Submit your ideas and your links, let our texts and our knowledge be bounded in the binary fissure. Let us become our own kings of infinite space; then let us build the bridges anew. Let the renewed era of Southland Tales begin.

Let the apocalypse reign, let what is past be swept away and let our “eyes reappear / as the perpetual star / Multifoliate rose” (“The Hollow Men”). Just as in Part 3 of Dante’s The Divine Comedy, let the souls of the saved in heaven gather in the form of a “multifoliate rose” around the deity—this film, not Kelly in case you’re a tad nervous.

As a remediated text, it defies expectations of what film should and should not be. The viewer’s experience of watching and response to the film is as vital as the film itself. This is not cinema of the dead, this is cinema of the living breathing world, and it’s calling you to participate. So far the work involving the film has been only hostile, but in that unfathomable hostility might not there be found some kernel of doubt? After all, if the film is a failure, why not just chuck it into the bin of other failures and move on. Why continue this vociferous assault? Unless those attacking the film so incessantly see some part in it that they can’t quite understand. Paralyzed by a litany of divergent meanings, they fly back, cursing the film and its creator with vitriolic hatred. In no small way then, Kelly’s dark vision of people depicted within this film is vindicated.

Kelly is not the first director to make movies that play like an experience, take a spin down Mulholland Drive if you want David Lynch to feed your mind through a blender. But Kelly is perhaps the most reviled for doing it. If there is a valid criticism to be levied against Kelly’s film, it’s that his ideas are introduced without much flair and abandoned with equal grace, but then perhaps that’s more the point of the world he’s imitating that a problem to be overcome.

So watch the film. Maybe you’ll hate it, maybe it will infuriate you, but I promise you it will not bore you. And when confronted with your own palpable response, try your best to express it. What angered you, infuriated you, made you happy? Conflict is welcome. All analysis begins with the self. So step through the looking glass, and report back with whatever you find.

Don’t just take my word for it, these are poor etchings on a digital page, a half-measured gonzo-fueled trip. Southland Tales is the supplier. This film is Gonzo. And like all true great Gonzo works of art, “the end result must be experienced. Instead of merely ‘read’.” —HST

Into the Twilight Kingdom (Conclusion)

So what are we to make of all this? The pieces have long been there for all to see, Kelly made sure to sprinkle them liberally about. But rather than embrace difference, and consider that which lay beyond traditional modes of cinema, the reaction was to disparage, to vilify and reject. It started in the critical sphere and like a rampant virus spread into the public. For too long has critical reception of this film been co-opted by critics who sound off like the charge of the light brigade, theirs is not to reason why, theirs is but to do and die.

Maybe the movie would have gone over better had it been titled Southland Fairy Tale, but then we seem so inured as a culture to the idea of the non-real, as if film were somehow an exemplar of reality. Sorry to disillusion, but quite the opposite in fact.

Perhaps what this film needs before it is truly accepted is its own bible. A literary gloss to annotate the film in one definitive volume—an authoritative schemata of Southland Tales. It may take all the fun out of the experience (James Joyce’s received no less than one hundred such attempts, all of varying quality; I imagine we can try at least once for Kelly).

That Kelly’s credibility has been all but expunged from the record on account of this film personifies more a lapse in critical jurisprudence than in Kelly’s talent, which is on display in abundance with this film had anyone bothered to look. Southland Tales is a modern masterpiece to study and scrutinize, not mock and consign to oblivion. Critical reception may one day alter in the film’s favour. Notice how for all their attempts to slay it, this is the beast that simply cannot die? Now that the avalanche of vitriol has settled, let us rediscover what has been lost. Let us return to the Waste Land, and see what we might uncover. These essays (and the probing words of others) hopefully mark the first tentative steps towards reclaiming what has been lost to ignorance.

The sad irony of the film is that you don’t need a time machine to have seen any of it coming. Correctly guessing that Clinton would be on the Democratic ticket is one thing, predicting NSA spying is quite another. Kelly taps into our collective dreamspace to speak to us. That we were unable to hear him speaks volumes of the state of our creative cultural unconscious.

Cinema is our collective dream space. It is our culture, our history, our wants, our dreams, our hopes and our fears; it is our past and will forever record our future. It’s the only semblance of logic we’ll ever get in this world and it’s our collective duty to protect this treasure, and to support those who do it best. Richard Kelly is one such figure, and no matter if I have to tell every person I know as many times as it takes until the idea is firmly lodged in their memory, this film is a masterwork, and it deserves our support.

People ask me why, with all the issues going on, why talk about film? The answer is because film lets us talk about the issues, and to propose new and novel ways of addressing issues. It may not provide answers, but that’s not the job of cinema, its job is to generate ideas. We may exist in a post-scarcity economy of film, with more movies than screens to exhibit them, but what we’ll never have in overabundance are ideas. They’re our most precious resource, and we’re throwing them away for the ease and efficiency of a metacritic score.

People ask me why, with all the issues going on, why talk about film? The answer is because film lets us talk about the issues, and to propose new and novel ways of addressing issues. It may not provide answers, but that’s not the job of cinema, its job is to generate ideas. We may exist in a post-scarcity economy of film, with more movies than screens to exhibit them, but what we’ll never have in overabundance are ideas. They’re our most precious resource, and we’re throwing them away for the ease and efficiency of a metacritic score.

In his earnestness to play the prophet, in trying to tear down the whole world and everything in it, Kelly undoubtedly consigned both himself and his project to futility. His yearning for an apocalyptic renewal that circumvents traditional narrative marked the doom of his message, if only because his readers were so inured by war and indoctrinated in scripture (of one kind or another). As the lack of commentary on this topic shows, Kelly could bring the parched mind through the social wasteland to the waters of cinematic and intellectual renewal, but he could not convince them to drink—nor, it seems, to make them even aware of what he offered them.

Much like Robert Aldrich’s misunderstood masterpiece, Kiss Me Deadly, Kelly’s film warrants a second glance. If Aldrich could be hailed in Cahiers du cinema as “the first director of the atomic age”, let Kelly serve as the first director of the gonzo cinema age.

Christ has died. Christ has risen. Christ will come again.

“Ladies and gentlemen, the party is over. Have a nice Apocalypse.”

—Southland Tales

If you like where my words are going, follow me on Twitter:

@binarybastard

Watch with:

Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

With T.S. Eliot open all the while

Support my work and the film:

Southland Tales Book 1: Two Roads Diverge (Bk. 1)

Southland Tales Book 2: Fingerprints (Bk. 2)

Southland Tales Book 3: The Mechanicals (Bk. 3)

Support both even more by commenting! Post questions, ideas, hypotheses, insights; hurl abuses at me (preferably at my work), at the movie, at anything, but comment nonetheless!

Fun Fact: That’s none other than Eli Roth getting gunned down while on the toilet during the police raid in a winking nod to Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction

Enigmas to ponder: What do we make of that bizarre boardroom scene, where the Japanese businessman loses more than he bargained for, a casualty of a six-inch margin of error? What is the point of this scene? Why the whole hand? Why the contract? Why need to take the hand in the first place?

Extra credit: Kelly makes use of a startling array of numbers in this film, at key intervals in the narrative. If anyone feels so inclined in undertaking some convoluted gematria, now’s your chance.

Addendum:

Some will no doubt accuse this essay of overreaching, or worse: fabricating connections that do not exist. The point is not whether Kelly actually had a copy of Whitman on him while filming Southland Tales (though if anyone can confirm…), the point is what Kelly’s film allows us to know and understand about ourselves and our culture. But now we have two competing accounts. Either you agree that the film has merit and Kelly by extension, or you agree with those who booed it out of Cannes (the only film I can think of which would merit such treatment is Exorcist: Part 2, any other time it’s just the ultimate disrespect). Before you decide, let’s use Occam’s razor and cut straight through the proverbial bullshit. What’s more likely: that Richard Kelly, through sheer luck and happenstance managed to put together a film that more than coincidentally touches upon every feature I’ve noted; or, that the writer and director (read: auteur) knew what he was doing, and more importantly what we was not doing? If you need proof that Kelly knows how to play by the rules and craft a Hollywood film, watch The Box, it’s about as close as I hope we ever get. Personally, I long for a return of the old Kelly, the brave and passionate frontiersman; who boldly dreamt to go where no one dared go before. So maybe he fumbled the delivery, let’s not crucify the poor bastard for it. Let’s hope he’s still out there some place, and let this essay serve as a vigil till he returns.

I’ve already gushed a little about this article on my twitter page. It’s one of the most inspiring things I’ve ever read. I’ve read it twice now, and I’m only just beginning to understand it all (I guess I’m referring to both the essay and the movie with that comment), so I’m sure it is something I will come back to again and again. With that said, there were a couple of ideas that were brought up in Abraham Riesman’s Vice interview that really brought the movie into focus for me, and weren’t mentioned in this essay.

I don’t think I saw any mention of the slowing of the Earth’s rotation in this article. Before I really started to “get” the movie, that was the key to my ability to suspend disbelief. Even before I understood all the factors contributing to the strange behaviors of the characters, it was this detail that allowed me to say, “Oh, they’re acting weird because of this bizarre environmental disturbance. Their internal clocks are all messed up.” It sounds so plausible that it ended up serving as a bridge for me between the more realistic and the more fantastic elements of the movie.

The other thing in the Vice article that really changed my understanding of the movie was Kelly’s description of Jericho as a false messiah, there to distract people from the real one. I had kind of put them both in the same category in my mind, and thought they were both there to fulfill the same function more or less. But once I understood this relationship between these two characters better, and the fact that they are there to perform almost opposite tasks, it just brought the whole Southland Tales universe together for me. Thinking about it now, it just makes the tensions between ALL the characters so tangible. I fell the pull and push working between the entire ensemble . . . the tides flowing in and out.

I’ll wrap it up now before I start making even less sense. But, again, great job on the article. Reading it has enlarged my world.

I purposefully tried not to retread any ground covered by the Riesman interview, simply because that ground had already been traversed so succinctly. And now, thanks to your fluent comment, I really don’t need to worry.

I also didn’t even pick up on the earth rotation thing, mainly because I couldn’t care less about film’s following logic. So long as the film knows it’s own rules and plays within them I’m willing to accept sound in space (ala Star Wars), or that an alien would look, sound and act exactly like an American circa 1970 (Superman, looking at you). I feel film is too often polluted by the introduction of logic and the necessities of “the real”.

After watching Lawrence of Arabia as part of the Prometheus discussion, I noticed a strong parallel between Rock’s bleeding tattoo in Southland Tales and Lawrence’s wounds bleeding through his shirt in Lawrence of Arabia. I don’t really have anything to add about that, just that it’s something I noticed and has been on my mind. I did a search online and was surprised to see that nobody else has seemed to make that connection.

I wonder if on this point we need to consider whether we can ascribe greater significance to the issue of intentionality versus coincidence, which I admit is a broader issue at work throughout this five-part series. How much are we allowed to “read into” these connections? I would argue so far as they go towards making a point. For example, it’s an interesting parallel that The Rock’s bleeding mark signifies him as the false messiah (according to Kelly’s extended backstory), just as Lawrence becomes a false messiah for the Arab people (not so coincidentally, this thinly-veiled rape scene you refer to is just another nail in the coffin for Lawrence’s psyche). Did Kelly mean anything by it, or are we just giving Derrida a headache?

Even though I finished working on “The Lost Year” last year, I continue to play up coincidences between Donnie Darko and my documentary (which was influenced by Donnie Darko). It’s a fun exercise, and I feel like it helps keep me connected to the ideas that inspired me to make the movie, but you definitely start to realize that anywhere you look for coincidences you’re going to find them.

You’re talking about a fine line between intention and accident, and it’s not uncommon to see otherwise rational people completely lose track of that line in their drive to understand art or life more deeply. I can’t help but wonder if what we’re witnessing are broader and more elaborate cultural/personal/universal archetypes than the standard ones we’re accustomed to discussing. And, if that’s the case, I also can’t help but wonder what it means that we intentionally or accidentally keep recreating the same powerful images.

Skype has launched its online-dependent buyer beta on the

entire world, following launching it extensively in the United states

and U.K. earlier this month. Skype for Internet also now works with Chromebook and Linux for immediate text messaging communication (no video

and voice nevertheless, those require a connect-in installing).

The expansion of your beta provides assist for a longer selection of languages to help you bolster that international

functionality